2. Heritage concepts, values and authorship – Considerations for making short heritage films

- 2.1 Main points

- 2.2 Film as part of the heritage dynamic

- 2.3 Heritage valuation

- 2.4 Heritage and authorship

- 2.5 Heritage categories

- 2.6 The use of metaphor

- 2.7 Conclusions

3. Guidelines for adult educators on how to produce digital stories

- 3.1 The filming process

- 3.1.1 Starting your filming: Write a script

- 3.1.2 Standards for video

- 3.1.3 Book of shooting: Actual start and matter of revision

- 3.1.4 Filming tips & tricks

- 3.1.5 Sound recording

- 3.1.6 Editing and producing

- 3.1.7 Terms of use

- 3.2 Excursus: Heritage authorship and documentary typology

- 3.3 Excursus: Key points of promotional video creation

- 3.4 The project platform

- 3.4.1 Introduction to project platform

- 3.4.2 Registration and video uploading to WAAT digital platform

4. Instructions on how to use digital stories in training activities and how to plan lessons

5. WAAT learning experiences and tips

1. Executive summary

WAAT aims to develop a modern and dynamic system of understanding and promoting cultural heritage through digital stories. Based on the subject cultural heritage WAAT shows how self-made short-films can be applied in adult education and at the same time WAAT contributes to disseminate heritage in its widest sense by introducing a heritage digital video platform. Besides a constructivist understanding of heritage we intend to offer an easy approach to the production of digital video stories. There is no need to have specific knowledge in filmmaking and you do not need special equipment. Based on this WAAT Guide for Educators, the camera of your mobile phone or tablet as well as basic user know-how are enough to produce short digital educational video stories and upload them on the WAAT digital platform.

You will have to choose one of the following four categories to classify your short video: tangible, intangible, digital and natural heritage. Tangible heritage includes buildings and historic places, monuments, artefacts, etc., which are considered worthy of preservation for the future. These include objects significant to the archaeology, architecture, science or technology of a specific culture. On the other hand, according to definitions of UNESCO intangible cultural heritage is a practice, representation, expression, knowledge or skill to be part of a place’s cultural heritage such as folklore, customs, beliefs, traditions, knowledge and language. Digital heritage is the use of digital media in the service of understanding and preserving cultural and natural heritage. And natural heritage refers to the sum of the elements of biodiversity, including flora and fauna, ecosystems and geological structures.

Dynamic, Constructivist Concept of Cultural Heritage

This chapter briefly introduces the constructivist understanding of heritage and links to filmmaking as medium to heritage preservation but at the same time as part of heritage formation. You will also learn about heritage valuation and considerations about authorship which are of specific interest for our open heritage short film platform.

Production of Digital Video Stories and the WAAT digital platform

The chapter guidelines for adult educators on how to produce digital stories introduces step by step the filming process and presents the WAAT project platform. The first part includes guidelines and hints concerning script writing, equipment, the filming process itself, sound recording, editing and production. You will also learn about what to consider concerning privacy, data protection, copyright and labelling of video material with licenses. After the general description of filming specifics for WAAT are addressed: Four forms of documentaries (ego documentary, observational film, participatory film and expository mode of making film) and key points of promotional video creation are briefly presented which seem relevant for the making of film about heritage. The second part introduces the WAAT digital platform and describes how to use it.

The next chapter outlines information and instructions on how to use digital stories in training activities, provides examples for the successful integration of digital stories and also presents a whole teaching programme including different aspects of using digital video stories.

Our Learning Experiences

Finally, a summary of the evaluation results and especially the experiences which we made during WAAT when developing and producing the digital stories and practical tips are presented.

Annex

In the Annex you’ll find good practices on applications of digital storytelling in education and good practices of short stories on cultural heritage, … [to be determined, other parts of the Annex to be mentioned].

WAAT (We are all together to raise awareness of cultural heritage) is a European Cooperation Project co-financed by the Erasmus+ Programme. The project consortium includes the coordinator Plunge public library (Lithuania) and the partners ICARUS HRVATSKA (Croatia), Quiosq (Netherlands), EGInA SRL (Italy), the Multidisciplinary European Research Institute Graz (Austria) and Centro de Educación de Adultos de Olmedo (Spain).

2. Heritage concepts, values and authorship – Considerations for making short heritage films

This chapter introduces key concepts to bear in mind when producing and sharing short films that are to be used to educate about cultural heritage. The video productions, that are to be shared on the online WAAT platform, will add to the exchange of European heritage values and promote heritage-related contact in an accessible and sustainable way, also making sure to further creativity and mutual respect. Key to the project is the notion of heritage as a dynamic of identification and belonging. This understanding of heritage goes beyond the idea of heritage as collections of static objects that travel through time, but rather emphasizes the ongoing interpretation of heritage – including all of its expressions, for example by means of film. In this view, we all perform heritage, and this text may help you to understand this role, its possibilities and its responsibilities.

2.1 Main points

Of particular importance to the project and its products is how we relate to concepts of heritage, the formation of heritage, heritage values and heritage authorship in relation to the production of short film. In this brief chapter, we outline these concepts.

We discuss stretching the concept of heritage from a static and object-oriented one, to one that is (also) dynamic and sociological in nature. When we depart from heritage as information-containing objects, we need to address the process of its values and valuation – that we are contributing to in the creation of film about heritage. The notion of authorship will help to see and guarantee multiple perspectives on the WAAT platform. Another important issue in the way we will be working, is choosing and connecting to heritage categories: what are they and how do we use categories for content on our platform that aims for maximal exchange? In addition to identifying the themes that are important for us in order to work with the video platform, we shall also consider some approaches for making film itself. For that reason, we will discuss different documentary typologies, as well as the use of metaphors to relate historic information to issues in contemporary society.

What is heritage, and why does it matter?

Practically all heritage specialisms have evolved from the notion of objects, documents or buildings as carriers of cultural – often historical – information. Early heritage professions have prioritized the preservation of such material heritage objects in order for this information to be passed down to ensuing generations. In this understanding, these historic information objects are unproblematic and legible: they function as containers of physical ‘proof’ of past processes, or ‘sources’ of past events that can (and should) be disclosed by media such as exhibitions, text or visuals so audiences can be educated by their content, ingenuity or beauty. For a long time, this mediation of heritage has been seen as a secondary process, being merely the transfer of monolithic historical information to nondescript audiences. The intrinsic value of the heritage object was believed to depend on the material state of the object, and heritage work focused on material vulnerable and the constant need of physical care.

This way of looking at heritage, that emerged in the nineteenth century and is still influential, strongly focusses on the act of bequeathing material objects to generations to come. From the late twentieth century onwards, heritage theorists and professionals have shifted their attention to another side of the heritage coin, namely the act of inheriting – of accepting and interpreting the past, not only by specialists, but by society at large. Now, heritage work consists not only of stabilizing material objects, but just as much in facilitating the process of identification with the past. Many of us choose the middle ground between ‘matter and the mind’ while some theorists are extreme in their positions, the Australian anthropologist and heritage expert Laurajane Smith, for example, states that ‘All heritage is intangible’ as she finds heritage a mental construct by definition.

In short: the general tendency in theorizing heritage has firmly shifted from ‘objects’ to ‘people’, from ‘past’ to ‘present’ and from ‘information’ to ‘value’. Rather than regarding heritage as sets of static historical information objects, we more and more approach it as an ongoing cultural dynamic that has temporary (and shifting) outcomes in the present. The key difference between these stances may be explained as the difference between an essentialist and a constructivist stance to heritage. In an essentialist understanding of heritage, we see heritage objects as carriers of historical information that is tied to, or ‘intrinsic’ to a material object, while a constructivist heritage concept proposes the ongoing construction (and deconstruction) of heritage values by people in the present.

According to constructivists, heritage is dynamic, complex and contradictory, as different groups of people form and act out their heritage constructions when they try to present and preserve their version as the most genuine or true. It follows from this view that heritage is not rescued from the past, but rather performed in the present and it is also – necessarily – an arena of debate and even discord. The constructivist view on heritage also implies that people are not only bound to heritage by knowledge, but also by their personal or collective memory, emotions, nostalgia, or a sense of identity and belonging (or separation!). An interesting observation is that not only positive feelings, but also strong negative emotions influence heritage valuations and stir heritage debate.

As a result of this paradigmatic shift, academic and professional interest in heritage has expanded from content matter specialisms to looking into heritage’s contemporary role in society. Without disqualifying the practices of heritage information that is vital in many contexts (such as archives and research collections), we find that in public exchange, a constructivist approach to heritage fits best with the complexity of society, with aims for diversity and social inclusion. We choose to understand heritage as a dynamic relation with the past and with each other, that we shape with semi-stable ‘objects’, and a wide array of expressions of content and value.

2.2 Film as part of the heritage dynamic

When we embrace this more sociological and dynamic stance to heritage in our project of producing and exchanging heritage film, there are a number of implications worth discussing. First of all, it is important to understand the status of film itself in the heritage dynamic – as this status depends from our understanding of heritage. WAAT Guide for Educators 8 We could argue that heritage that is seen as static and robust, is not influenced by its mediation. Seen as such, the medium (such as film) only transmits heritage information, its role seems neutral, not influencing the heritage itself. But when we accept the interpretation and valuation by contemporary society as part of heritage formation, our short films are more than just heritage ‘access points’. Rather, they are part of the process of shaping heritage, thereby integral to the process of heritage formation rather than merely transmissions. We could conclude that in the light of a constructivist understanding of heritage, our films are an intrinsic part of the heritage itself.

2.3 Heritage valuation

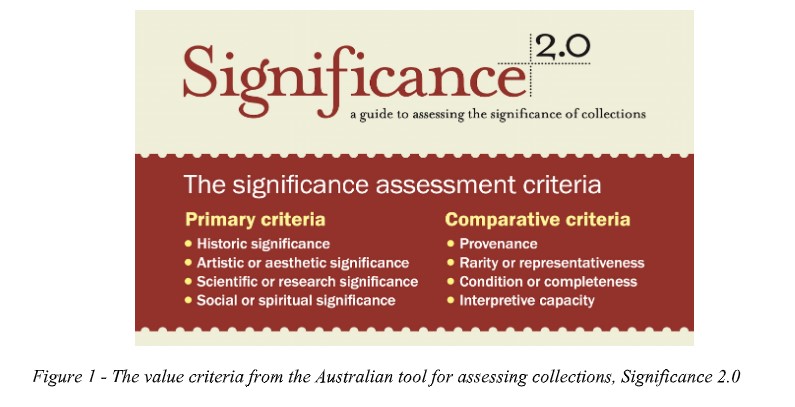

Secondly, when we understand our film platform as being formative and creative in the heritage dynamic, this also urges us to think about the way heritage may be interpreted and valued by all participants. It is important to realize that heritage values are always chosen and weighed, often implicitly. In the heritage profession, initially in the domain of tangible heritage and museums (but also in other sectors such as interior and landscape), systematic tools have been developed to analyse and explicate heritage values. This is often done by proposing a methodological investigation into the heritage at stake, then scoring the heritage object against a set of preconceived heritage value criteria. In the last twenty years, such valuation research has been expanded from merely historical, archival and material research to investigations that also take into account how heritage functions in society, identifying and questioning heritage communities and mapping relevant networks. Value criteria have been extended from historical, aesthetic and scientific values to more societal values such as emotional and spiritual values, as well as values that refer to identity and memory. On our film platform we hope that the whole bandwidth of values will be taken into account and that participants are triggered to think of local or personal values that may not conform to the existing valuation instruments.

It is interesting that, as a result of this development (but also under the influence of theorizing immaterial heritage), authors like the Dutch linguist Rob Belemans have questioned the systematic investigation of heritage values. After all, as heritage is more and more seen as relevant to certain groups of people (and not others), so that universal valuation criteria and -claims are problematic at least. Different groups of people relate to ´their´ past and culture differently, sometimes contradictory, as they add value and emphasis according to their own needs and identity. Heritage values are likely to be local and contingent to certain groups.

This resonates with the critique on patterns of heritage valuation by Laurajane Smith, who links certain (historic and aesthetic) values to national pride and grand narratives of the nation state. She suggests that a choice for these generic values over the ‘softer’ and more diverse societal values favours the majority over smaller, unheard groups in society. She identifies uneven ways of valuating heritage, giving certain groups in society a stage for their identity – while others remain in the shadows. Belemans and Smith show that the valuation of heritage can be problematic, as it is often still done by representatives, often the elite. With our film platform, we hope to modestly contribute to a more democratic valuation of heritage.

2.4 Heritage and authorship

By now, the heritage sector acknowledges the entwinement between heritage objects and contemporary society, rendering heritage complex and multifaceted. Still, professionals in the sector need to decide on significance, valuation and decisions need to be made to perform heritage in contemporary society. The same goes for us in developing our heritage short film platform. How do we facilitate expressions from viewpoints as diverse as we aim for, and still guaranteeing some quality, honesty and respect? A transparent way of dealing with this in our project, could be an emphasis on authorship. We have seen that heritage cannot be seen apart from the communities it stems from, and therefore, a notion of the identity and needs of such related group are important to express. Transparency of the ‘heritage author’ not only expresses the societal dynamic of heritage, but it also gives room for different values and viewpoints. By shedding light on the author and his or her motives, we acknowledge that heritage performances are local and communal by definition, and that even goes for heritage communities consist of renowned academics with an international network! By being clear about our own identity, goals and perspective, instead of claiming the past, we share ‘just’ our version of it, always curious of different values, identities and attitudes. In this way, heritage is more than collections of facts, things, monuments or places: it is a form of contact and an invitation to respond. Different ways of doing this are exemplified by some documentary sub-genres in which the perspective of the author takes different shapes (for more details see 3.2):

-

- the ego documentary, which is mainly autobiographical and organised around the person of the maker

-

- the observational mode, where the film maker shows something without comment, but is still being present as observer

-

- the participatory mode, in which the film maker interacts with the subject under discussion

- the expository mode of documentary, where the film maker explains something authoritatively without being involved not visible

2.5 Heritage categories

Another implication of a dynamic and societal understanding of heritage that we need to be aware of in the WAAT project is the categorization of heritage – and therefore the categorization of our films. Historically, the heritage discourse developed in the wake of (and alongside) collections domains such as archeology, archival studies, monument care and museology. In the late 20th and early 21st century, these heritage domains were refined and expanded, either by very specific collection domains (mobile heritage, interiors, industrial heritage etcetera), but also by ‘new’ broader categories such as immaterial heritage, landscape and natural heritage.

At the moment, heritage consists of a great number of different categories and specialisms. It is important to consider that these categories were determined by history; they emerged around physical objects, sites or documents, but also as a result of historic events (periods of national prosperity or trauma) and also in relation to specific functionality in society such as relation with (administrative) processes such as governmental archives. Many of these heritage categories have their own body of knowledge, specialists, institutions and heritage perspective.

The thing they have in common, is that they reason from the nature and ontology of ‘their’ heritage (collections and disciplines) rather than the needs or identity of groups in society. An exception to this may be the recent and emerging category of immaterial heritage as well as the ecomuseum, which understands heritage as social and dynamic in nature – as something that is always shaped and passed on by its performance. In a societal and dynamic approach to heritage, it would pay of to organize and categorize heritage according to shared human experiences or themes, rather than existing institutions of disciplines. Users could choose more than one category for their film, we could choose to expand categories in the process and finally, categories do not have to be mutually exclusive.

2.6 The use of metaphor

For inspiration, not only for the choice of categories on the platform, but also for making the short movies ourselves, the WAAT project can draw inspiration from the use of metaphor by the Dutch ethnologist and museologist Gerard Rooijakkers. Rooijakkers is closely connected to Museum ‘t Oude Slot in Veldhoven in the south of the Netherland, and he developed many heritage projects based on the concept of the cultural biography. This is an anthropological concept that points to the social life behind apparently lifeless objects, rendering such object as ‘biographical’ and capable of telling human narratives. In his projects, Rooijakkers connects past to present by choosing metaphors that connect to historical content, places and objects, but also resonate with contemporary society and present-day experiences. As these metaphors need to connect different worlds and different experiences, they cannot be too literal or strict; but need to be open enough for such connections. On the other hand, they also should not be too vague or unspecific. For example, for a certain rural region of Brabant in the South of Holland for example, Rooijakkers choose the metaphor of ‘hospitality’, that is typical for the identity of the region in the present and also relates to the historical content he referred to. Rooijakkers metaphors often bridge historical facts with human experience and tend to be poetic – and therefore recognizable and specific.

2.7 Conclusions

Rather than the static set of objects under the care of professionals, the complexity of heritage is much better understood as the ongoing calibration of value in the form of the many reflections on heritage by anyone who relates to it. As such, ‘heritage is cared for by anyone who cares’; its custodians are as diverse as are their valuations. This view renders heritage dynamic and pluriform and its access democratic.

In an essentialist view on heritage, professionals that are most knowledgeable are logically authorized to disseminate heritage as static information about the past. The mediation of this essential heritage information is then always secondary to the heritage itself – it tends to have the status of documentation or education. A constructivist understanding of heritage, on the other hand, renders heritage dynamic and contemporary; it privileges the many ‘heritage stories’ over the ‘heritage object’. As a result, heritage interpretation becomes part of the heritage itself, and we accept that these interpretations are subjective, even contradictory. Following this idea, heritage practices, such as our film platform, aims to be open for multiple perspectives and discussion.

When we see our film platform as part of the ongoing social heritage negotiations, the perspective of the maker is important. We are not disseminating unequivocal and unambiguous heritage ‘truths’, but rather interpretations, values that are relevant for certain groups. Declaring our role and perspective as author, and being part of a larger debate, invites others to do the same and adds to the reciprocity of heritage that we want to be part of. A maker of films has many options to emphasize (or obscure) his or her role as author, and we would like to invite our makers to reflect on these possibilities and experiment with them.

Another consequence of our heritage understanding is the way in which we categorize heritage – as well as the films we will be hosting on our platform. A dynamic and sociological understanding of heritage calls for categories that connect to shared experiences in contemporary society, rather than the object-oriented structures that were envisioned by specialists, institutes and subject matter. It could be inspiring to look into the use of metaphor by Gerard Rooijakkers as a way to connect past to present and fact to story. After all, society continuously expresses and expands itself in their heritage rather than curating an unalterable past into an undefined future.

References

Bazelmans, J.G.A. 2006. ‘Value and Values in Archaeology and Archaeological Heritage Management: A Revolution in the Archaeological System.’ Berichten van de Rijksdienst voor het Oudheidkundig Bodemonderzoek 46 (2006): 13–25.

Rana, J., Willemsen, M., Dibbits, H. 2017. ‘Moved by the Tears of Others, Emotion Networking in the Heritage Sphere.’ International Journal of Heritage Studies 1–12.

Rooijakkers, G. 1999. ‘Identity Factory Southeast: Towards a flexible cultural leisure infrastructure.’ Esitelmä Jyväskylässä 1–5.

Rooijakkers, G. 1999. ‘Het leven van alledag benoemen.’ Boekmancahier 41 275–90. Russell, R., Winkworth, K. 2009. Significance 2.0: A Guide to Assessing the Significance of Collections. Collections Council of Australia Ltd.

Smith, L. 2006. Uses of Heritage. New York: Routledge.

Smith, L. 2011. All Heritage is Intangible: Critical Heritage Studies and Museums. Amsterdam: Amsterdamse Hogeschool voor de Kunsten.

Versloot, A. 2013. Op de museale weegschaal: collectiewaardering in zes stappen. Amersfoort: Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed.

3. Guidelines for adult educators on how to produce digital stories

According to Wikipedia “digital storytelling refers to a short form of digital film-making that allows everyday people to share aspects of their life story.” The combination of written and spoken words, photographs, illustrations, video clips, and sound adds a new dimension to sharing stories or disclosing information. For our WAAT platform we determined the length of a digital story to be three to five minutes.

In the following you find further information on the filming process with a variety of instructions, examples, tips and tricks and an introduction into the WAAT project platform.

3.1The filming process

3.1.1 Starting your filming: Write a script

After deciding on what you want to show and who or what will be the main protagonist of your digital video story (DVS), elaborate your idea and explicitly state your wanted outputs in a written script. The script might include the following aspects:

- theme or topic of your DVS, goals and objectives you want to achieve

- specify what, when and where you plan to film

- detailed description of the story as well as all narration and/or dialogues

- sounds you plan to exploit and for what purpose

- planned length

- scenography settings

- props you want to use (objects used for filming scenes – e.g. a candle, a chair, a photo, etc.)

3.1.2 Standards for video

The cameras on most modern mobile phones are able to film in full HD resolution (1920 / 1080 pixels). For publishing videos on different media please consider the length of your video. Our digital short stories, with a length of three to five minutes, can’t be published on Instagram or Twitter without making adjustments. They can be published on various websites, including our platform and on YouTube. Have in mind that YouTube uses video in HD resolution and in codec H.264 or MPEG-4 (Advanced Video Coding-AVC), used for compressing video files (automatic adjustment on YouTube). Each social media outlet has its own specifications; digital stories from our platform will need to be adjusted to specific media.

Basic rules for filming with any type of camera:

- Film in full HD resolution 1920 x 1080 pixels. Other dimensions are also suitable: 1280 x 720 (720p), 1920 x 1080 (1080p), 2560 x 1440 (1440p) and 3840 x 2160 (2160p).

- Aspect ratio is 16:9 (auto adds pillarboxing if 4:3).

- Max file size is 8 GB or 15 min., whichever is less.

- Accepted video formats include: .MOV, .MPEG4 and .MP4.

Tips:

-

- Don’t shoot vertical videos (!).

- Write a script.

- Use a tripod (basic tripods or adapted tripods for smartphones).

- Don’t use digital zoom (this will reduce video quality; better get closer to the subject).

- Have good light (the most accessible lighting source is sun).

- Keep camera/smartphone charged.

- Pay attention to the white and black balance, try not to make the video too bright or too dark.

- Check the settings on your mobile phone. You want to adjust to 1080p at 30 frames per

second (fps). If you have optical image stabilization your footage will be filmed without twitches and you might avoid using additional equipment like Rig stabilizer.

- Orientation is important – rotate your phone and keep it horizontal.

Think about framing, about composition and arrangement of objects or people in front of your camera. This is the mode you direct your viewers to look at what you’ve intended to show. Like in paintings, composition plays an important role. For example, putting your object in the centre might create a moment of tension, while placing it on one third of a frame creates more of a naturalistic moment.

Here are a few more advices for taking a well-composed shot:

- Shoot simple shots without any dynamic movements around a subject or object that you are filming. That way film viewers will know what to pay attention to.

- If you shoot a group of people, individuals can be positioned at various distances from the camera. The whole group doesn’t need to be positioned at the same distance from the camera.

- Avoid shooting subjects with a white wall behind them because the shots could look uninteresting and flat. Position your subjects at least a few feet away from the background to get a depth of field behind a subject.

- You can make the scene you are shooting more interesting, for example, by putting some posters or paintings on the wall, by putting a special tablecloth or a vase on the table, or by turning on a room lamp or by putting some houseplant in the scene.

- Persons that you are filming should be positioned considering the shot frame. Their faces should not be too low or too high in the composition.

- If you have a visible horizon line in your shot or another long horizontal line, try not to position a person that you are filming in such a way that this horizontal line intersects with the head or the neck of that person.

- Try to avoid bright colours in the background of your shot, so that the attention of the viewers stays on the person you are filming.

- You can contextualize the shot. For example, let the viewer see the person that is talking about some topic and near that person an object or a specific location which is related to the speaker. E.g., the museum curator could talk in front of the object he is talking about.

3.1.3 Book of shooting: Actual start and matter of revision

In the filmmaking process the term ‘frame’ refers to still images and for the purpose of script making it can be seen as a list of scenes that all together make a film scenario.

Write your book of shooting through a frame-to-frame mode, like a list of shots which you plan to film (remember comic books as simple guidelines).

In each frame position object and/or narrator, plan dispositions and filming in total or detailed frames. All filming instructions should be clear and easy to follow.

3.1.4 Filming tips & tricks

A cameraman/camerawoman will need instructions written in a storyboard.

If your mobile phone has an optical image stabilizer, you won’t need an external stabilizer. If not, consider investing in an optical electronic stabilizer, otherwise twitches will be too obvious and hard to avoid. Also, it will come in handy, if you want to move not just forward and backward from the object of filming but also around it. One of the oldest rules of filming, the so-called 180-degree rule, teaches us not to confuse the viewer by suddenly changing position from the left to the right of a character in a frame-to-frame sequence. By using a stabilizer, you can walk around the back of one of the characters and change their positions in a more natural way.

Another general rule is to avoid light to the back of the subject (filming into the light).

Setting up filming should be adjusted to the specific situation and prior defined goals (according to your target audience):

Example 1: Tangible immovable heritage in landscape setting/natural heritage (e.g. castle).

Start filming with wide shots (also called long shots) and slowly narrow to full shot – the castle being in the centre of the right-hand 1/3 of the composition. Take into consideration the light situation – ideally it is a cloudy day with sun above the clouds so the natural diffusive light is creating a clear but soft shot; if there isn’t a bright noon-like light, the sensors of the camera wouldn’t react. Check the exposure value in the video app’s settings and adjust accordingly. After filming the medium shot you might want to get close and film some specific close-up shots, exposing the details like texture of the walls or some specific ‘privileged’ view that is uncommon or non-accessible to non-experts, placing the camera on low angle.

Example 2: Tangible movable heritage indoor (e.g. 3D museum object)

When shooting indoors, make sure you’ve secured additional sources of lights, led light with diffuser. Use white lighting set on 50 Hz and light object as per many sides as possible, but also with diffusion light. You might use diffusion fabric placed on reflectors or reflectors directed toward white sheets placed at sides of objects, so the light will reflect off them. Avoid shadows because details wouldn’t be visible in the objects’ normal condition; you might perceive shadow as part of an object although that is not in fact the case. Place the object on fabric of different colour (white objects might look good on a grey pad), but make sure it is neutral so the object gets full attention.

Think about how you want to film moving the object, or present its use for example. If you have a stabilizer you might move around the object; if not, put the object on a rotating plate, if possible, to show it from all sides.

Example 3: Intangible heritage (e.g. folk songs)

Intangible heritage will include filming the carrier of their content, usually a person as performer. That person is the focal point of filming but her/his specific parts, depending on the intention; to present a dance (movement), to present only a song (voice), language (voice and facial expressions as well as gestures). Setting up proper lighting will again be the challenge.

3.1.5 Sound recording

If possible, use an external, portable sound recorder with microphone (audio in) input, and a separate bug microphone. The advanced version, for our purpose, is to use a portable sound recorder with two to four channels that enables recording two to four persons or sounds at the same time. Also, you can use a quality voice recorder (dictaphone) for which you don’t need a mic. During the editing process these sound recordings will be synchronised with a visual record made by the camera. In that way you will get a sound which has a better quality than the sound recorded with the camera. Whenever it is possible use an external sound recorder which is not built into the camera or mobile phone. If you want or if you need to record sound only with your camera, then the camera should be positioned very close to the person who is talking or to any other sound source you want to record.

Here are a few advices for a high-quality sound recording:

- If you record sound in a closed space, shut all doors and windows, so that you don’t record unnecessary sounds from the background.

- A mic which is built into a camera also records the background sounds. So listen very carefully and try to silence or neutralise these sounds.

- It is best to record certain interesting sounds by positioning the camera or sound recorder very close to them – for example, the sound of the opening of the creaking door or the sound of the purring or meowing of a cat. During the film editing, these sounds can be used for interesting effects and creation of atmosphere.

- It is best to use quality headphones when you record sound, because in that way you can monitor the sound and you can correct or adjust the sound recording settings on the spot.

3.1.6 Editing and producing

Transfer all recordings into separate folders on your computer, both audio and video files. Start by reviewing all recorded video materials. Import them into your chosen software for editing and synchronize with recorded sound.

The recommendation for editing software is VideoPad Video Editor. It has all functionalities for quality film editing; it has a free version for non-commercial use; it is very reliable and its user interface is very similar to other quality film editing software which means that you can easily transfer skills and techniques acquired by working with this software to other film editing software.

The homepage of VideoPad Video Editor is: https://www.nchsoftware.com/videopad/index.html

There is a possibility to download the commercial version of this software on this page, but if your work is intended for non-commercial use, you can download a free version of VideoPad Video Editor here:https://www.nchsoftware.com/videopad/vpsetup.exe.

Free software for editing:

Windows:

- Canva – https://www.canva.com/create/videos/

- Moovly – https://www.moovly.com/ – free, but with a 20-movie limit for the free tier.

- Kapwing – https://www.kapwing.com/video-editor

- Wondershare Filmora – https://filmora.wondershare.net/

- Movavi – https://www.movavi.com/

- Openshot – https://www.openshot.org/

- Davinci Resolve: https://www.blackmagicdesign.com/products/davinciresolve/

MacOS:

-

- iMovie (integrated with MacOS)

- Davinci Resolve: https://www.blackmagicdesign.com/products/davinciresolve/

- Openshot – https://www.openshot.org/

-

- For small/simple projects with only a few clips, we recommend downloading a video editing application on your phone. Here is a summary of the best free and paid video editing apps:

3.1.7 Terms of use

This section is divided into three categories:

-

- General Data Protection Regulation rules regarding private and personal information of persons presented in video

-

- Copyright issues connected with a specific heritage object and its ownership

-

- Copyright issues regarding filmmaker and related authors

-

- Labelling video material with licenses that will define its future reuse

1. Personal privacy and regulations of use of personal data consent

European legislative framework that regulates use of personal information for archiving purposes and historical research is Regulation (EU) 2016/679 General Data Protection Regulation: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=celex%3A32016R0679

Persons who will be shown in our films have to give their consent in written form that they are participating consensually and it is to be clearly defined which personal information they allow to be published about them. Name and surname are considered to be personal information as well as any other information that can identify a person.

If you have a GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) officer in your institution, check the following suggested informed consent form so that it can be adjusted to specific institutional needs. You will have to translate it into the language you are going to use in communication with your participants.

Suggested elements of informed consent form:

-

- data controller: Official title of your institution

- contact e-mail: Your official e-mail or e-mail of the GDPR officer, if your institution has one

- The personal data we collect: Your name and surname, phone number etc. (specific needs to be expressed here)

-

- The purpose of collecting your personal information is for the use in educational and promotive video material that the xxx (name of institution) is preparing as part of the WAAT project.

-

- By signing the consent form you agree:

-

-

- That we collect, process and preserve the following data for internal project purposes: Your name and surname, contact e-mail, phone number and address.

- That we may contact you via given contact e-mail and/or phone number.

- That we publish your name and surname in our educational and promotive video.

-

-

- By signing this consent, you may:

-

-

-

- make a request for rectification, so that we correct wrong data or make other amendments.

- make a request for erasure of your data and by doing so we will not publish also the material

you’ve donated.

- complain regarding the way that we are processing your personal data that you’ve shared with us.

-

-

-

- Our responsibilities:

-

-

- We will not lease your personal data to any third parties, unless directed by effective laws. Only data that we are going to publish is your name and surname, if the project manager and filmmaker decide that it is necessary for the quality of the video.

- We protect your data from unauthorized access and manipulation of any kind.

- We will keep your personal data for a minimum of five years (due to the procedures we have to comply during an EU-funded project).

-

-

- Personal data that we collect and process:

| Name and surname | ……………. |

|---|---|

| Date of birth | ……………. |

| Contact address | ……………. |

| Contact e-mail | ……………. |

| Contact phone number | ……………. |

-

- Data provider: Name and surname (printed)

-

- Signature: Signed by data provider

-

- Date and place

-

- Institutional proxy: Name and surname (printed)

-

- Signature: Signed by the legal proxy

-

- Date and place

2. Copyright issues connected with specific heritage object and its ownership

-

- Some European countries have legislative regulation that governs the rights of owners of cultural heritage objects (see lists of protected cultural property) regarding their rights to financial or other form of compensation, if that object is used or published in public space. Discuss with the owners of the heritage object you wish to film about their possible expectations. In most cases, since this will be educational, creative and promotional video publicly available to promote awareness of cultural heritage importance (e.g. ‘non-commercial purpose’) it will be enough to thank the owner at the end of the video or in accompanied metadata and give credit in such mode.

-

- Suggested elements of informed consent form

-

-

- I confirm that I’m the owner of the object (title) and am consensual to include the abovementioned object in the film (title) prepared by the institution (name of institution) as part of the WAAT project (‘We are all together to raise awareness of cultural heritage’) activities. I am aware that this video will not have commercial purpose and I don’ ask for any financial compensation.

- (State other agreements – if owner wants his name accredited at the end of the film, or in metadata)

- Signature owner

- Signature institution

- Date, place

- Institutional proxy: Name and surname (printed)

- Signature: Signed by the legal proxy

- Date and place

-

3. Copyright issues regarding filmmaker

-

- If your employee who works on this project doesn’t have written in his/her basic work contract the obligation to make such films as part of regular activities or if your institution doesn’t have general regulations that all audio-video material created during working hours belongs to the institution, then you’ll have to make additional consent regarding transfer of copyright on the institution, in which you’ll state that the filming is part of the WAAT project activities and that the author(s) will not be additionally financially compensated, other than the one that is already agreed in their project contracts.

-

- That doesn’t mean that author(s) of the film don’t need to be credited – the authorship is a moral right and non-transferable. In the film or accompanied descriptive metadata the name(s) of authors must be presented.

-

- Also, the author(s) have to be consensual that, if the institution will have need in the future, there is a clear transfer from them to the institution concerning the following rights: the reproduction right (the right to make copies), the right to create adaptations, or derivative works (‘derivative work’), the right to perform and display the work publicly, the right to distribute copies of the work to the public.

4. Labelling video material with licenses that will define its future reuse.

-

- It is in our interest as well as a sign of professionalism and best practice to label our videos accordingly to licenses we wish to assign to them. There are six different Creative Commons license type options; for more details see:

https://creativecommons.org/about/cclicenses/

-

- For purposes of the WAAT project platform we are building and films we suggest the following license:

-

- : This license allows reusers to copy and distribute the material in any medium or format in unadapted form only, for non-commercial purposes only, and only so long as attribution is given to the creator.

-

- includes the following elements:

-

- BY pic – Credit must be given to the creator NC pic – Only non-commercial uses of the work are permitted ND pic – No derivatives or adaptations of the work are permitted

3.2 Excursus: Heritage authorship and documentary typology

Key to the WAAT project of producing and sharing short heritage films is the notion of heritage as a dynamic of identification and belonging. This understanding of heritage goes beyond the idea of heritage as collections of static objects that travel through time, but rather emphasizes the ongoing reception and interpretation of heritage by contemporary society. Seen as such, heritage is a social process rather than (also) a collection of objects.

This process includes the selection and valuation of heritage, as well as all of its medial expressions. It involves heritage as constantly performed by people and institutions a certain way. Together, such (groups of) people and institution are in fact authors of heritage. This sense of authorship is key to expressing the diversity of heritage: different authors have different views and together they express the riches and complexities of interpretations of the past.

When media are used to reflect on heritage, such productions are seen as part of the heritage performance. This is why, in this project, it is important to understand and apply the concept of heritage authorship. When making film about heritage, we can learn from the fields of visual anthropology and cinematography, where the role of the author has been theorized profoundly and has been applied in different ways.

In the next section, four documentary forms are discussed that presents the maker in different ways: the ego documentary; the observational film, the participatory film and the expository mode of making film. These modes were chosen as they seem the most relevant for the making of film about heritage. They may broaden a maker’s options of making film about heritage, and it invites them to think about presenting or hiding their own perspectives and views. For a more complete list of documentary typology, see Bill Nichols, Introduction to Documentary. 1 Bill Nichols, Introduction to Documentary. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001

Modes of documentary (a shortlist)

-

- Ego documentary:

The ego documentary is a subjective documentary mode that concerns a theme that is of personal interest for the maker. He or she is the key figure in the story and always leads the narrative, that is often an investigation into a private (family) matter, their own identity or a contemporary societal issue. It is the personal connection, emotion or activism of the maker that draws the viewer into the story. The maker is being portrayed visually or is present through a voice over. Examples of this mode are The Origin of Trouble (Tessa Pope, 2016) and Notes towards an African Orestes (Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1976). - Observational film:

These ‘fly on the wall films’ keep the film-maker out of the frame, merely documenting their observations. They typically leave out comments, and refrain from using a voice-over. The maker seems invisible in the scenes and seems to be reduced to their choice of subject and angle. Examples of this type are the classic Berlin: Die Symphonie der Großstadt (“Berlin, Symphony of the Great City”; Walter Ruttmann, 1926) is De Kinderen van Juf Kiet (“Ms. Kiet’s Children”; Peter Lataster & Petra Lataster-Tisch, 2017), which shows how a school teacher communicates with her pupils, often the children of recent immigrants, through verbal and non-verbal means.

- Ego documentary:

-

- Participatory film:

A term coined by documentary theorist Bill Nichols, participatory mode (also known as interactive documentaries) describes a type of documentary in which the maker impacts on the events that are recorded. The maker departs from his own observations and questions that may be presented as genuine and important ‘truths’, and captures the interactions that result from these observations and questions. An example of this mode is Vilshult (Tom Roest, 2018), about the filmmaker’s research of an omnipresent decorative photograph sold by Ikea and also many of Michael Moore’s documentaries, like Bowling for Columbine (2001), are participatory in nature.

- Participatory film:

-

- Expository mode:

The expository mode is the type of film which most people will traditionally associate with the word “documentary”. Also referred to as the “Voice of God film”, an expository documentary records a subject with argumentative logic, presenting objective facts or observations. Usually, a convincing narrative determines the structure of the film, with artificial elements such as sound effects or music mixed in. A narrator often speaks directly to the viewer. An example of this mode is the BBC series Blue Planet (and most other nature documentaries).

- Expository mode:

Obviously, the traditional way of documenting heritage would rely on the expository mode of making film, recording heritage as stable and unambiguous, but the other options for structuring film may invite makers to experiment with more subjective ways of telling heritage stories. It could be an advantage to be transparent about the maker and their motives, rendering heritage more open to debate and to other perspectives.

A final note: it is important to make a distinction between the author of the film and the author(s) of the heritage at hand – the related heritage communities – although these two often coincide.

References:

Bill Nichols, Introduction to Documentary. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001 Links to the films mentioned above:

- Berlin: Die Symphonie der Großstadt (Walter Ruttmann, 1927): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LdFasmBJYFg&t=1668s

- Blue Planet (Alaistair Fothergill & David Attenborough, 2001): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s4aQqx_Zo00 (fragments)

- Bowling for Columbine (Michael Moore, 2001): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SDl-atwBzf0 (trailer)

- De Kinderen van Juf Kiet (Peter Lataster & Petra Lataster-Tisch, 2017): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dB0SQbodTig (trailer)

- Notes Towards an African Orestes (Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1976): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xs7JaIhxnbw&list=PLHe0rBwDmYVMlfuKiReFBWSgT34G 98l4X

- The Origin of Trouble (Tessa Pope, 2016): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MxjaNgm47SA (trailer)

- Vilshult (Tom Roest, 2018): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pD0EPtBGuOU&t=1s

3.3 Excursus: Key points of promotional video creation

The primary and fundamental purpose of a promotional video is to promote a particular product, service, or event.

Our goal (in the case of WAAT) is to translate different concepts of cultural heritage into video, which also meets the guidelines for promotional videos.

When creating promotional videos, one of the main things we need to pay attention to is the target audience. We need to be open to the problem that people, who use our platform, want to solve.

Therefore, we need to frame our product as a solution to that problem. And that’s where we face the challenge of conceptualizing most of our content as a product. Most of our services are intangible, in other words – we trade knowledge / information or emotion.

Before we start creating a promotional video, we need to identify the key points we want to draw our viewer / client’s attention to. To distinguish these points, it is necessary to know the features and benefits of the ‘product’, and how they affect each other.

In the case of WAAT, we have fairly clear features, e.g.:

-

- Condition(state, intactness, material authenticity, material integrity)

- Ensemble (completeness, unity, cohesion, conceptual integrity, conceptual authenticity, contextual authenticity)

- Provenance (documentation, life story, biography, source, pedigree)

- Rarity and representativeness (uniqueness, exemplar value, prototype, type exemplar)

We can define the benefits for the viewer in terms, such as:

Knowledge, information, joy, perception of cultural identity, self-discovery in a cultural context, souvenirs, excursions, etc.

-

- The hardest part is how to convey it in video format. Therefore, promotional videos fall into additional categories, such as product videos, intro videos, product launch videos, event videos, explainer videos, video ads, recruitment videos, FAQ videos and testimonial videos.

-

- As an example, we can use the Plungė District Municipality Public Library.

-

- Features are:

-

-

- Legacy of Counts Zubov

- The oldest building in Plungė

- Representative facade

- Cultural heritage object

-

Benefits are: Private and group excursions, possibility to buy souvenirs, possibility to pick up books.

By highlighting these points in a video, we ensure that the viewer / client receives not only beautiful visual information, but also interest, in this case coming to visit the library located in the cultural heritage and perhaps at the same time giving away books that she/he borrowed a long time ago. Therefore, features and benefits are integral aspects of creating a promo video.

It is also suggested to pay attention to the ‘golden’ rules of the promotional video:

-

-

- Multiple angles.

- Short and sweet.

- Tell a story.

- Quality.

- Make a shooting script.

- Pay attention to acoustics and lighting.

- If you are doing a Q&A video, prepare questions in advance.

- Visit the place you want to film.

-

References:

-

- Russell, R., Winkworth, K. 2009. Significance 2.0: A Guide to Assessing the Significance of Collections. Collections Council of Australia Ltd.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L6FfJNSOiAU

https://promo.com/blog/what-is-a-promotional-video

3.4 The project platform

3.4.1 Introduction to project platform

Digital platforms nowadays are developing new ways to package and provide access to information and shaping the trends in user experience of digital services. Digitalisation has transformed our world and the cultural environment. Information is made available over the Internet and we carry the World in our pockets. Digital access to knowledge by means of the Internet is possible in a wide range of forms.

Main purpose of the platform is to function as a tool to upload heritage videos, and operate as a knowledge platform. The digital platform is mainly oriented to function for experts, professionals and practitioners in the fields of heritage as well as for adult educators and learners, NGOs and various communities in order to make videos and present the cultural heritage. It is well adapted to mobile devices, and also has an active virtual map which shows where in Europe the stories were taken.

Aims of the digital platform:

- To facilitate the learning process for adult learners.

- To raise awareness of cultural heritage.

- To improve ICT skills for adults such as: to create personal accounts, to upload digital stories and to set the GPS location.

3.4.2 Registration and video uploading to WAAT digital platform

You need to register on the WAAT digital platform to be able to upload your own content. It is very easy to register and to log in every time afterwards. All you need is a valid email address.

Registration steps:

- In the upper right corner is the button ‘LOG IN’, you click on it.

- You can join existing members, but first you need to register. Underneath the window you find a small link ‘Register’, click on it.

- Then you need to decide on a username and insert your email address. After you click the button ‘Register’ you will receive an email, click on the link.

- The link guides you back to the WAAT platform where you need to set a password. Click the button ‘save password’.

- The window appears with a link ‘log in’. You have to insert your username or email and your password. Also, you can choose the option ‘remember me’ to stay logged in.

Once you are registered and logged in to the platform you are available to upload videos.

Uploading videos steps:

-

- Select ‘upload video’ in the menu bar.

- Choose a brief and fitting title for your submission.

- Describe your submission (please provide short and specific information about the object/video and provide GPS coordinates where the video was taken or which country, city, region or town heritage comes from), use max. 200 characters for description.

- Insert the link of your video from YouTube, Vimeo. You can also upload a video directly from your computer.

- Choose and upload a thumbnail which rightfully presents your submission.

- Write down fitting tags, which best present your submission (e.g. heritage, tangible, travel, Lithuania).

- Choose the right category for your submission (tangible, intangible, nature, digital).

- Press the ‘submit button’, and if you are transferred to the display of your submission, then the process was successful. You will receive an email confirming that your video has been successfully uploaded to the platform.

- If the video does not meet all the instructions and standards, the platform administrators will contact you.

4. Instructions on how to use digital stories in training activities

Educational videos have become more and more popular as many institutions are using them as a tool to enhance learning. According to Herreros (1987), using video resources in class helps the students to store significant learnings as images, sounds and words which stimulates learning. In addition, Bravo (2000) states that the use of educational videos enhances the teaching-learning process. Hence, in this Guide, it will be described how to use video material to learn about cultural heritage which will be a useful tool for those who want to get an enjoyable learning experience and to develop the learning process.

4.1 Examples of digital movies on cultural heritage used for education

There are many schools which work on cultural heritage through videos. Students record videos so that they learn about heritage and also show this to others using social media or other channels. Using video resources has an advantage over traditional learning, as you can perceive in a few minutes what would take a lot more time to read. Besides, students get more motivated to work on different subjects when using ICTs, as they are used to play video games in their daily lives. Let’s see some examples of videos used for education:

-

- The following link https://www.elchaplon.com/el-ceip-mararia-divulga-en-cuatro-videos-el- patrimonio-cultural-de-femes shows four video resources recorded at a school. They are about the cultural heritage of the surroundings of the school.

- In this link: https://www.colegiosanagustin.net/descubriendo-el-valladolid-de-los-austrias/ the school ‘Colegio San Agustín’ tells about the cultural trip of the students to learn about the ‘Valladolid of the Habsburg’.

- The ‘Consejería de Educación de Castilla y León’ which is in charge of education in the region of ‘Castilla y León’ in Spain, organizes a school contest called ‘Monumento a la vista’, where students participate sending videos about monuments in ‘Castilla y León’. The contest is for 11 to 15 years old students: https://www.educa.jcyl.es/es/informacion/concursos-premios/monumento-vista.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pwx_aIQBgYk: The ghost of the Castle of Miranda is visited by some students from the Primary Education Center ‘La Charca’ and it explains them the history of the castle and surroundings. It was recorded by some students of the school to be presented to the rest of the pupils. Intangible cultural heritage is presented as the legend of the ghost is told in the video. Besides, it takes us to different places of the castle and surroundings which is classified as tangible cultural heritage.

- In this video https://iessantamarialareal.com/el-video-de-2o-de-eso-finalista-en-el-concurso- monumento-a-la-vista/ the students of the secondary education center ‘Santa María la Real’ from Aguilar de Campoo tell us the history and most important facts that took place in a Monastery which is a Nacional Monument in Spain. It is addressed to students who are taking bilingual studies. It shows tangible cultural heritage.

- In this video https://profesionaljdeabajo.wordpress.com/popurri/turismo/rutas-turisticas/el- valladolid-de-los-austrias/ a guide presents the Valladolid of the Habsburg with some videos. It can be used by anyone to teach about this or by any person who would like to learn about this matter. It can be used for learning or travelling virtually. It is tangible cultural heritage edited by José F. de Abajo.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FBfUU5RmJPA: José Fernando de Abajo R. describes the modern history of Spain: Valladolid, XVI and XVII centuries, to cultural centers or tourists who want to learn about tangible cultural heritage. Valladolid is presented during the XVI and XVII centuries when the grandsons of the Catholic Monarchs spread their legacy in the biggest regions of Spain and Europe ‘Castilla y León’.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jK-RisXiqSM: This video is about all the cultural heritage of India. It is directed to students, not only Indians, also students from other countries. In the video the traditions, language, dress, religions and so on are explained.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_VI5wJbwQe8: This video has been done by Qatar Museums. In the video it is demonstrated how teachers explain Qatar cultural heritage to their students. It is a practical example for teachers of how to teach cultural heritage in general.

4.2 Teaching programme

1. Title

‘The House of Habsburg in Valladolid’

2 Justification

Spain was an empire during the reign of the House of Habsburg in Spain and Valladolid was one of the most important cities in Spain becoming the capital of the country from 1601 a 1606. For that reason, it is a part of the cultural heritage that it is taught to Spanish students in Spain and specially, in the region of Castilla y León.

3 Introduction

This teaching programme has been developed so that students can actively interact and learn about cultural heritage in the city of Valladolid. Each student will turn into a ‘cultural investigator’ so that they are involved in the creative programme.

4 Objectives

-

- 1. General objectives

-

-

-

- (Chapter IX, article 66, of the Organic Law 3/2020 of 29.12.)

- Develop the personal abilities in the communicative areas and interpersonal relationships.

- Develop the abilities to be involved in social, cultural, politic and economic life and implement their right to live in a democracy.

-

-

-

- 2. Objectives of the teaching programme

-

- Understand the historic period.

- Read maps and place historic facts.

- Identify and distinguish civil religious architecture.

- Get to know the different kings of the House of Habsburg in Valladolid.

- Learn about the cultural legacy of the 16 th century.

- Learn about the period of time when Valladolid was the capital of Spain and all the changes related to it.

- Promote cooperative work.

- Value and respect the cultural heritage of Valladolid.

- Understand the historic period.

5 Contents

-

- What to achieve

- Historic and chronologic period

- The House of Habsburg in Spain

- Kings of the House of Habsburg in Valladolid

- Cultural legacy of the House of Habsburg in Valladolid

- Valladolid capital of Spain

- What to achieve

-

- How to achieve contents

- Identify the different kings of the House of Habsburg in Spain.

- Identify the different kings of the House of Habsburg in Valladolid.

- Place the more representative buildings of the House of Habsburg on a map.

- Identify the period when Valladolid was the capital of Spain.

- How to achieve contents

- Attitude to achieve towards contents

- Make aware of the need for conservation of cultural heritage.

-

- Positive attitude towards investigation and new ways to learn.

- Value group and cooperative work.

- Enjoy cultural trips.

Value the historic and cultural importance of Valladolid.

-

- Make aware of the need for conservation of cultural heritage.

6 Methodology

An active, dynamic and cooperative methodology among students will be implemented. Constructivism will be the base of learning and starting from the previous knowledge of students, a meaningful learning will be conducted. This means that they will show their interests and needs and so all the activities will be connected to them. In order to do this, active and interesting activities will be developed so that they help them gain understanding.

Methodological principles:

Active methodologies place the students at the centre of the learning process and make them the centre of this rather than just passive information receivers.

Constructivism and emotional education are the guide for the teaching process so that the multiple intelligences of the learners will be developed. People construct their own understanding and knowledge of the world, through experiencing things and reflecting on those experiences (Bereiter, 1994). The teacher makes sure he/she understands the students’ pre-existing conceptions, and guides the activity to address them and then build on them (Oliver, 2000).

Constructivism’s central idea is that human learning is constructed, that learners build new knowledge upon the foundation of previous learning (Bada, 2015). For this reason, starting from a brainstorming, the teacher will check the previous knowledge of the learners.

All the activities carried out and the contents will be explained at the beginning of the session. Warm- up, lead-in, questioning and cool-down activities, among others, will be carried out during it. The learners will be grouped depending on the activities and this will benefit their social abilities.

7 Timing

Three weeks, twelve hours divided as follows:

- Session 1 and 2: Two hours

- Session 3: Three hours

- Session 5: Two hours

- Session 6: Three hours

8 Tasks

-

- SESSION 1

-

- Previous knowledge activities:

-

-

- Brainstorming. Who are the Habsburgs? How long were they the Kings of Spain? How many of them ruled in Spain?

-

-

-

- Warm-up activities:

-

-

-

- Using a digital board, all the Kings of the House of Habsburg will be introduced.

-

-

-

- Lead-in activities:

-

-

-

- The students will look for information about the name and date of birth of all the Habsburgs in Spain.

- Then, they will check the video https://youtu.be/J0iQZ9MXnOE where all the information about this dynasty is explained.

- Finally, they will be told they will have to create a video about the Habsburgs in Valladolid but first, they will have to write a script including the following aspects:

-

-

-

-

- Theme or topic of your DVS, goals and objectives you want to achieve.

- Specify what, when and where you plan to film.

- Detailed description of the story as well as all narration and/or dialogues.

- Sounds you plan to exploit and for what purpose.

- Planned length.

- Scenography settings.

- Props you need to use.

- Filming accessories you might need.

-

-

-

- SESSION 2

-

- Previous knowledge activities:

-

-

- Our students will be asked some questions about the previous lesson so that we remember what we learnt the day before.

- Brainstorming: Which of the Kings of the House of Habsburg were born in Valladolid? How many of them lived in Valladolid? Where was Philip II baptized? Are there any monuments in Spain related to this period? Are there any monuments in Valladolid related to this period?

-

-

-

- Lead-in activities:

-

-

-

-

- A video about the art in Spain during the reign of the Habsburgs will be watched. https://youtu.be/M_oLpzSAjhM

- A video about the story of the Habsburgs in Valladolid will be watched https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FBfUU5RmJPA..

- The teacher will introduce the different kinds of cultural heritage: tangible, intangible, digital and nature

.

- After the videos, they continue writing the script for the video they will have to create.

-

-

-

- SESSION 3

-

- Warm-up activities:

-

-

- We will watch a video about the art in Valladolid during the reign of the Habsburgs https://drive.google.com/file/d/1dnRs-39Q_gAZiFb-FhNWC6Vz7_rTdSxA/view?usp=sharing

-

-

- Lead-in activities:

-

-

- In groups they will create a video with the length of three to five minutes with the most important art in Valladolid during that period. They will have time to go around Valladolid for recording the video about the art in this city.

- Previously, the teacher will let them know the standards for the video and some tips like:

- Don‘t shoot vertical videos (!).

- Write a script.

- Use a tripod (basic tripods or adapted tripods for smartphones).

- Don‘t use digital zoom (this will reduce video quality; better get closer to the subject).

- Have good light (the most accessible lighting source is the sun).

- Keep camera/smartphone charged.

- Pay attention to the white and black balance, try not to make the video too bright or too dark.

- Check the settings on your mobile phone. You want to adjust to 1080p at 30 frames per second (fps). If you have optical image stabilization your footage will be filmed without twitches and you might avoid using additional equipment like Rig stabilizer.

- Orientation is important – rotate your phone and keep it horizontal.

-

-

- SESSION 4

-

- Previous knowledge activities:

-

-

- What have we learnt so far? The students will answer this question for some minutes.

- Brainstorming: Can you name some monuments of Valladolid of this period?

-

-

-

-

- Warm-up activities:

- Was it fun recording the video? Did you have any problems? Did you learn from doing this activity?

- The students will be taught how to edit and produce the video and they will have time for this at the computer room. As it is a short video, they will have time enough to edit it.

-

-

-

- SESSION 5

-

- Final project tasks:

-

- The learners will show their videos to the rest of the participants.

9 Conclusions

This didactic unit can be used with any kind of learners from teenagers to adults. The main objective is to teach about cultural heritage in Valladolid. Besides, the learners will learn how to use digital materials and how to record videos.